The Regent Queen had very much insisted upon the setting up of a great festival of bulls and reeds in Cordoba, in honour of the Grand Duke, for which there had not been occasion during his stay in Madrid, due to the mourning of the Court. These celebrations, always popular in Spain, benefited in those years, more than ever, of the royal favour, such was the enthusiasm with which Philippe IV had liked them, even up to the point to participate personally himself, sometimes together with his favourite the Count-Duke.

Like the medieval tournaments, it was an activity reserved to the nobles, but highly prized among all classes. The Papal Bull of Pius V, “De Salutis Gregi Dominici”, excommunicating every prince who allowed the celebration or attended “those bloody and shameful spectacles where bulls run in the public squares” had never been published in Spain, by express intervention of Philippe II. And the truth is that the profound clericalism of Cosimo III did not prevent him from attending a show which had been described by the Pope as “more akin to the devil than to faithful christians.”

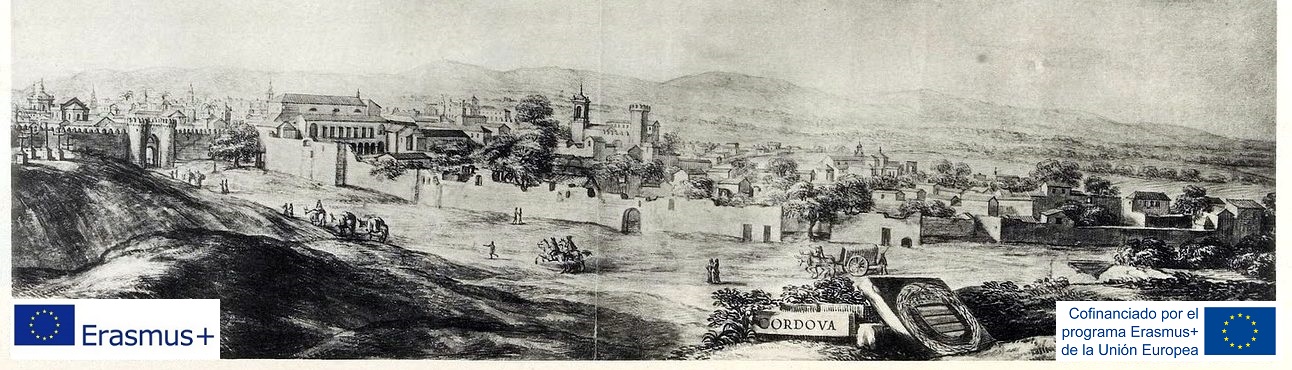

On the morning of the 12th the duke approached the Corredera Square, already decorated with wooden stands around its perimeter and colourful hangings on the balconies. From the place arranged for him in the House of the Corregidor, he could see the “encierro”, moment in which the cattle, guided by the halters and the foremen were introduced in the bullpen. Although this was not really part of the festival, the lads had the opportunity to have fun and show off their skills by teasing the bulls with the capote and dodging them with a waist-slouch. Magalotti describes without qualms the custom of sacrificing to the people the bull that arrived last. This one, after being dizzied with the capes, was released to the dogs (bulldogs or Alans), moment that was taken advantage of to cut the nerves of the hind legs, so that the bull fell, dragging the legs on the ground and then, says Magalotti, “all the riffraff, with daggers and swords, jumped on him, being fortunate the one who can separate the largest pieces.” Then, three mules dragged it out of the square, always followed by the people. That day, in attention to the Duke, there were three bulls that ran such destine.

Once ended the “encierro”, the duke returned home, where he attended mass and received the visit of the bishop. In the afternoon a carriage brought him back to the square, already crowded with people, as much as the balconies with ladies, “all beautifully dressed.” A few years later, the Countess D’Aulnoy, travelling through Spain, will describe in a much less dry style than Magalotti’s, the impression made on her by the main square of Madrid prepared for a bullfight: “The gentlemen greet the ladies who are on the balconies, free of their mantles. They are adorned with all their jewels and with the best clothes they have. You cannot see other than magnificent fabrics, tapestries, cushions and rugs trimmed with gold. I’ve never seen anything more dazzling.”

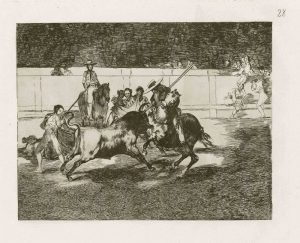

Very ceremoniously, the corregidor offered the Duke, in a silver tray, the key of the bullpen, as was customary to do with the King, so that he threw it to the usher and the party began. But as the duke refused the privilege, the same corregidor threw it to the usher, who immediately released the first bull. The chronicles of Magalotti and Corsini give us the name of the noblemen who participated in the bullfight, all on horseback, as well as a meticulous description of the clothing, demeanour, courage and dexterity of each one.

After the first “rejoneo”, performed by Don Pedro de Hinestrosa, “knight twenty-four”, there took place the most beautiful parade of couples of riders flying long banners (which they called “comets” for their long tail), followed by the feast of reeds, Hispano-Arab heritage, and skirmishes, which the Florentines found similar to their “carousel” parties.

Next, went on the bullfighting with don Pedro de Hinestrosa, Don Francisco de los Rios (“whose horses – says Magalotti – were not only the best of the party, but the best you can see”) and Don Gonzalo Antonio de Ceu . In total, eleven bulls died that afternoon. Meanwhile, the duke and his courtiers were continually being gifted with trays of “delicate jams”, fresh water and chocolate, and the orchestra of horns and fifes mixed their sounds to the ovations of the crowd and the bellowing of the beasts.

When, very late, the party ended, those gentlemen that had attended him that day, accompanied the duke home. We will never know how he judged in his heart the show performed in his honour; but, in comparison with the jousts celebrated in Florence, in the Plaza de Santa Croce, known by him, that delirious mixture of death and jubilation, that exaltation of luxury and blood, must have looked to him as coming from an older and more barbarous world than his. Perhaps that night he went trembling to his prie-dieu in search of the peace of prayer. Perhaps the harsh words of the papal anathema or the tender exhortations of San Francisco to the creatures and wild beasts of the country resounded in the depths of his soul. Or perhaps, that last descendant of a decaying race, whose former bright had been extinguished forever, that worthy representative of a coarse, materialistic and prudish religiosity, went to bed without further ado, and, with a satisfied mood, he slept the whole night.