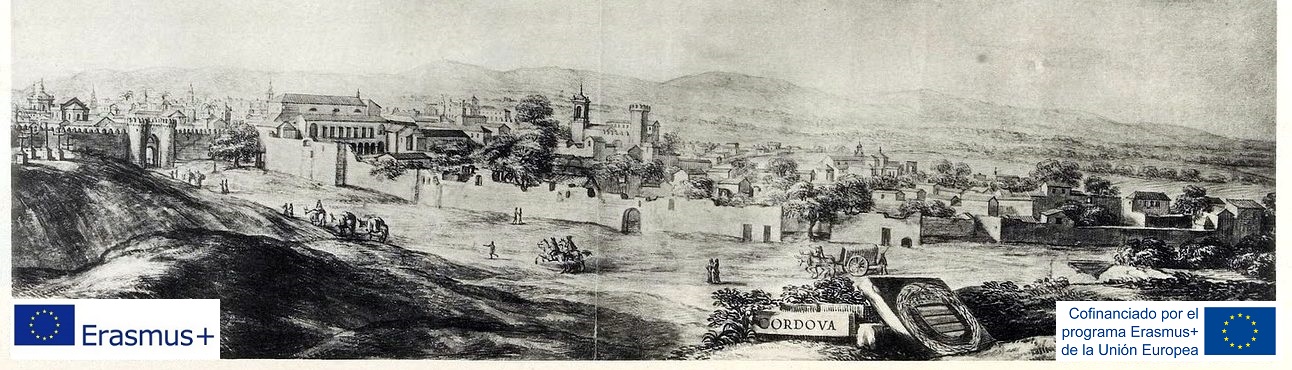

Another day of his stay in Cordoba, the duke wanted to visit the famous monastery of San Jerónimo de Valparaíso, which was one and a half league distant from the city. He set out in a six-seat carriage in which some of the leading noblemen of Cordoba were admitted and to which five other carriages were added along the way.

The place in which the monastery is located, sheltered by the mountain range, looked singularly charming to them and, by their description, it must be even more so in those days than it is at present, since the vegetation that crowded the hillside, from the convent to the plain, included “a wonderful forest of sweet lemons and oranges around which the enclosure wall is developed.”

It was not so long ago that the monastery had received a royal visit, that of Felipe IV, accompanied by his brother, the infante Don Carlos. Almost a century before, King Felipe II had spent the Holy Week there in 1570, the year in which Cortes were held in Córdoba. He was accompanied by his nephews, the Archdukes Ernesto and Rodolfo, the future Emperor. However, the main historical interest of the monastery for the Duke Cosme and his courtiers focused on the stay of the Catholic Monarchs, and particularly of Queen Elizabeth, who resided periodically in it during the Granada War, being the only woman who, in all the centuries of history of the monastery, by special papal dispensation, had placed his feet inside the cloister. In his chronicle, Magalotti even attributes by mistake to the Catholic Monarchs the foundation of the monastery, which, as is well known, owed its birth to the Fernández de Córdoba.

The monks did the delights of the duke by showing him the gifts of the Catholic Queen, treasured throughout the centuries: a small ivory box, inlaid with ebony, containing an ivory comb and a “rosta” or straw fan, which she had used during her stay in Valparaíso. The fact that the queen decided to leave the monks objects of such personal use is consistent with the chronicles, according to which, “she treated the friars as brothers and with such familiarity and affection that was caused of amazement”.

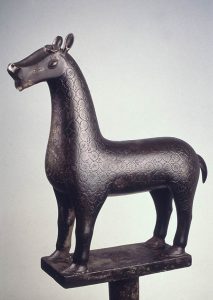

In another room the Duke saw a portrait of King Boabdil and the arms he wore when he was taken prisoner in Lucena by the Marquis of Comares, Don Diego Fernandez de Cordoba, another of the great benefactors of the Monastery. Unfortunately, they have not left us any description of the most important donation that this same sir made to the monastery: the altarpiece painted by Alejo Fernández for the main altar of the church, which the duke and his courtiers were due to see “in situ” and from which there is nothing left today.On the contrary, the chroniclers carefully describe the delightful view they enjoyed from the monastery’s terraces, which covered the hillside and the whole countryside, until making out some of Sierra Nevada in the distance. Somewhat melancholy, however, it sounds to us today its reference to a place where the horses grazed, of which they say: “this place is called Córdoba la Vieja because from some buildings, whose ruins are seen from here, they say that once there was a city”; for the city, about which memory was so completely lost, was none other than Medina Azahara. Perhaps one of the courtiers or the duke himself happened to stop before the precious bronze fawn that in those days adorned the fountain of one of the cloisters, as centuries ago it had done in the source given by the Byzantine emperor to Abderramán III. It maybe he knew the fawn that is kept in the Bargello Museum in Florence, or the gryphon of the Cathedral of Pisa, both also survivor to the ruin of the Cordovan caliphate. In any case, the most probable thing is that they did not appreciate the style of these works, given that when they visit the Lions Yard in the Alhambra, they will refer to the famous sculptures that support the fountain cup simply as “some poorly sculpted marble lions.”From the terrace, the illustrious visitors went to the prior’s rooms, where they were entertained with jams prepared with water and chocolate. And from there, to the Library, where the treasure of manuscripts and incunabula does not seem to have impressed much the inflexible Magalotti, whose tastes were directed more to the field of experimental science, as evidenced his position as secretary in the “Accademia del Cimento” Florentine .At last, the duke decided that they all were to make the descent of the monastery on foot, given the peacefulness of the day and the pleasantness of the place. According to the chronicler, the day did not seem typical of the month of December in which they were, but one of the most beautiful and temperate in April, a comment that will undoubtedly not be strange to the people of Cordoba today.